Humble Beginnings of CSBC

HUMBLE BEGINNINGS

HUMBLE BEGINNINGS

Court Street Baptist Church, originally known as the African Baptist Church, is regarded as the mother church of all the city’s Black Baptist congregations. The Court Street Baptist Church congregation dates its beginning in 1815 while worshiping at the First Baptist Church (white). Court Street Baptist Church was not organized as a separate church until 1843.

The present edifice designed by R.C. Burkholder, a local white architect, was constructed exclusively by black laborers many of whom were church members. Construction began in 1879 and was completed in 1880.

Court Street Baptist Church was esteemed as Lynchburg’s chief black architectural landmark, with its spire the tallest object gracing the downtown skyline .Today the church stands as a testament to the perseverance, enterprise, and faith of a godly people.

The Court Street Baptist Church was added to the National Register of Historic Places in June of 1982 and is also on the Virginia Landmarks Register.

STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE

STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE

Court Street Baptist Church is Lynchburg’s chief black architectural landmark. Begun in 1879 and completed in 1880, it was then the largest church edifice in the city, with its spire the tallest object on the downtown skyline. The church was designed by a local white architect, R. C. Burkholder, but black labor was used exclusively in its construction, and black artisans were in large part responsible for the decorations and furnishings of the auditorium.

Although a number of nearby residents initially objected to the building of a black church on what was then one of Lynchburg’s most fashionable residential streets, as construction progressed the white community began to applaud the congregation for its accomplishment. When the church was completed, the editor of the Daily Virginian spoke for all in declaring that “it stands an almost imperishable monument to the vigor, enterprise and religious zeal of the society to which it belongs.”

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

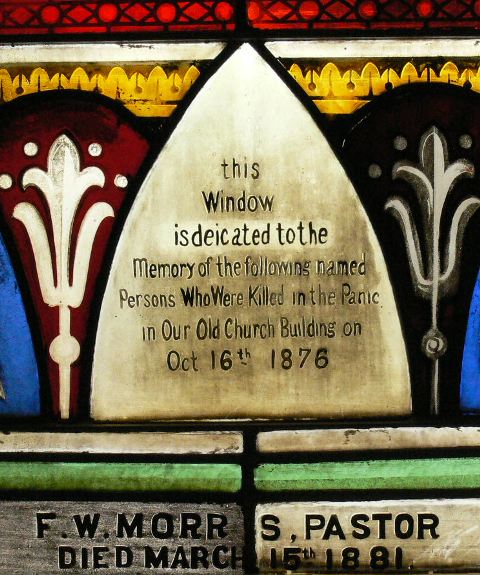

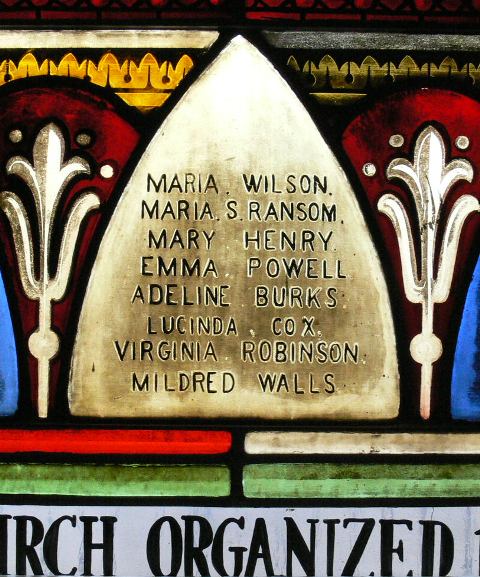

On March 5, 1879, the citizens of Lynchburg were informed by the Virginian that “The Court Street Baptist Church, colored, at which the calamity occurred last fall, is being pulled down. The material will be used in a new church building, corner of Court and Sixth Streets. The lot was purchased by a citizen.” Between those concise lines lay a story of so much local interest that there was no need to repeat what everyone in town already knew. The “calamity” was indeed that. At a wedding in October 1878, an alarm was given that the crowded balconies were collapsing.

On March 5, 1879, the citizens of Lynchburg were informed by the Virginian that “The Court Street Baptist Church, colored, at which the calamity occurred last fall, is being pulled down. The material will be used in a new church building, corner of Court and Sixth Streets. The lot was purchased by a citizen.” Between those concise lines lay a story of so much local interest that there was no need to repeat what everyone in town already knew. The “calamity” was indeed that. At a wedding in October 1878, an alarm was given that the crowded balconies were collapsing.

Although the alarm was false, the ensuing melee resulted in the deaths of eight persons, who were trampled and crushed in the attempt to evacuate the building. Remembrance of that tragedy would find expression in the new building, where the iron supports of the balcony were made to extend below the basement to rest on solid rock. Behind the short notice that the lot was purchased by a citizen lay another story, one amplified by a historical sketch published by the church in 1960:

At that time, Court Street was where the homes of the prominent and rich white residents lived, and during the days of slavery they wanted to keep the Negro slaves near them in their worship services in order to observe their loyalty. However, when Freedom came, they had no further interest in them, and they wanted to force the Negroes to move their worship place from the prominent Court Street residential section of the city. But, since Negroes had worshipped on that street since it was the center of the town, the colored congregation was just as determined to remain on Court Street with the Church.

At that time, Court Street was where the homes of the prominent and rich white residents lived, and during the days of slavery they wanted to keep the Negro slaves near them in their worship services in order to observe their loyalty. However, when Freedom came, they had no further interest in them, and they wanted to force the Negroes to move their worship place from the prominent Court Street residential section of the city. But, since Negroes had worshipped on that street since it was the center of the town, the colored congregation was just as determined to remain on Court Street with the Church.

When it was learned that the black congregation intended to purchase a lot near the site of the old building the owner was offered a substantially larger amount by several whites to prevent the sale. This attempt failed however for the trustees had placed a deposit of $100 on the lot and had entered into a binding agreement to pay the balance of $2,400.00 within a certain amount of time.

Pressure was then put on the city’s banks and loan associations to refuse a loan for the congregation. This ploy was thwarted when the church members gathered their savings together and contributed enough to cover not only the purchase price of the lot, but also several thousand dollars in construction costs for the actual building. That the congregation could come up with such an amount on short notice is explained in the church history by the racial tension that prevailed in Lynchburg in the Postbellum era:

At a time when colored people did not trust the white people too much, most of the members of the church had their savings at home between mattresses or wrapped in socks and small bags stuck in the attic or in cavities over the mantles.

After the lot was purchased, the cornerstone was laid and in reporting o that occasion, the editor of the Virginian informed his readers that “this, we understand, is to be quite a handsome structure, and one of the largest in the state. Mr. R. C. Burkholder is the architect and the building will be finished by October 1st.” That deadline was not met however and the building was not completed until July 1880. During the interim the local papers furnished a number of articles describing the building and the progress of construction.

After the lot was purchased, the cornerstone was laid and in reporting o that occasion, the editor of the Virginian informed his readers that “this, we understand, is to be quite a handsome structure, and one of the largest in the state. Mr. R. C. Burkholder is the architect and the building will be finished by October 1st.” That deadline was not met however and the building was not completed until July 1880. During the interim the local papers furnished a number of articles describing the building and the progress of construction.

In one of these accounts, the editor of the Virginian informed his readers that he had visited the carpentry shop of “J. W. Green, colored (who) showed us a pulpit, designed and made by himself, for the Court Street Baptist Church.” The editor described the pulpit as “of solid walnut, with an Italian marble top, and covered with silk, with pendants and tassels. He closed his account by wondering ”how so neat a job could have been made entirely by hand and concluded that the church might have paid more money for worse work in New York or Boston. Despite the condescending tone of the editor’s report, his account and others like it helped persuade the citizens of Lynchburg that the church would be an asset to the city and not a liability.

In one of these accounts, the editor of the Virginian informed his readers that he had visited the carpentry shop of “J. W. Green, colored (who) showed us a pulpit, designed and made by himself, for the Court Street Baptist Church.” The editor described the pulpit as “of solid walnut, with an Italian marble top, and covered with silk, with pendants and tassels. He closed his account by wondering ”how so neat a job could have been made entirely by hand and concluded that the church might have paid more money for worse work in New York or Boston. Despite the condescending tone of the editor’s report, his account and others like it helped persuade the citizens of Lynchburg that the church would be an asset to the city and not a liability.

As for Court Street, it continued for many years to be regarded as a fashionable address, and a number of large mansions, as well as churches for white congregations were soon built nearby. Largely unchanged since its completion, the modified Italianate building is the largest remaining example of the work of architect and builder Robert C. Burkholder. Burkholder came to Lynchburg just prior to the Civil War. After serving the Confederacy, he returned to the city and became in the ensuing decades one of Lynchburg’s most prominent architects.

The building houses a congregation that was formally organized in 1843, when the African Baptist Church officially separated from the parent First Baptist Church. As was typical in the antebellum South, the ministers of the new congregation continued to be appointed by the parent white congregation, and white custodians attended all its services. An old theatre, purchased for the new group, was remodeled and served the congregation until a fire destroyed it in 1858.

The building houses a congregation that was formally organized in 1843, when the African Baptist Church officially separated from the parent First Baptist Church. As was typical in the antebellum South, the ministers of the new congregation continued to be appointed by the parent white congregation, and white custodians attended all its services. An old theatre, purchased for the new group, was remodeled and served the congregation until a fire destroyed it in 1858.

The congregation then moved to a converted tobacco factory that stood nearby on Court Street between Fifth and Sixth streets. This temporary church was replaced in 1867 by the building which was demolished after the tragedy.

Largely through the efforts of the minister and members of Court Street Baptist Church, the Virginia Baptist Convention authorized the establishment of the Lynchburg Seminary in 1886. The Reverend Phillip Morris of Court Street Church served as the first president of the institution, which was later named the Virginia Theological Seminary and College. Its main building, Hayes Hall, and the home of one of its most distinguished graduates, Anne Spencer, both in Lynchburg, are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

During the later 19th century, the church organized a number of Sunday Schools in outlying sections of Lynchburg to serve members who might not otherwise have been able to attend worship services. From these several schools, a number of separate congregations were later organized. Court Street Church is regarded as the mother church of all the city’s black Baptist congregations and still houses a large and active congregation, well aware and appreciative of the building in which they worship. In addition to its own considerable architectural and historical interest, the church building forms an integral component of an impressive grouping of late 19th-century churches on the hill above Lynchburg’s downtown business district. It is, in fact, one of the two oldest structures in this “ecclesiastical compound, and its spire is still a notable, if no longer dominant, feature of the Lynchburg skyline.”

During the later 19th century, the church organized a number of Sunday Schools in outlying sections of Lynchburg to serve members who might not otherwise have been able to attend worship services. From these several schools, a number of separate congregations were later organized. Court Street Church is regarded as the mother church of all the city’s black Baptist congregations and still houses a large and active congregation, well aware and appreciative of the building in which they worship. In addition to its own considerable architectural and historical interest, the church building forms an integral component of an impressive grouping of late 19th-century churches on the hill above Lynchburg’s downtown business district. It is, in fact, one of the two oldest structures in this “ecclesiastical compound, and its spire is still a notable, if no longer dominant, feature of the Lynchburg skyline.”